Creating a psychologically safe workplace requires emotionally intelligent leaders who can model specific behaviors.

Psychological safety, an interpersonal concept, pioneered in the 1960s, then largely abandoned until the late 1990s, gained enormous traction again around 2015, and refers to an environment or relationship in which members aren’t afraid to speak up, be themselves, admit to their mistakes, or offer honest feedback.

Psychological safety is important because it is the entry point for belonging and thus helps to unlock not only well-being and resilience, but also the benefits that diversity and inclusion bring to your teams and organizations. It also helps to frame the conversation about failure.

Psychological safety is the entry point to belonging. Belonging is the desire to feel connected to others, to feel cared about and cared for by others, and to be part of groups that are important and matter to you. Belonging is one of our core psychological needs and it’s fundamental to human motivation, well-being, and happiness.

When we have to stop being who we are or change who we are or adapt to who we think we need to be—because we are looking to fit in—it shows we don’t feel like we belong, and it’s enormously wearing. It’s really exhausting to not be our whole selves.

That exhaustion might only show itself in subtle ways at first, but it compounds over time, and can eventually develop into larger problems, such as burnout. The biggest misconception about burnout is that the cause and solution are internal, and that it’s up to the individual to monitor, prevent, and work through independently.

In reality it’s more of a complex workplace-leader-team-culture issue and that’s the lens that we need to start looking at it, instead of thinking we can yoga our way out of it.

Our growing understanding of Psychological Safety

Amy Edmondson, the Harvard Business School professor of leadership and management who is widely credited for the term’s renaissance in recent years, says our understanding of psychological safety has grown immensely in a relatively short period.

“There’s been more and more research put out there from different kinds of workplaces that show a relationship between psychological safety and other things like learning, or reporting mistakes, or innovation,” Edmondson says. “There is research that suggests it’s not about the challenge or the stress of your job that predicts burnout or leaving, it’s the absence of someone to talk to about the challenge or the stress.”

The other big change she’s observed in recent years is the growing understanding of psychological safety’s connection to diversity and inclusion. “Now that we have an even greater mandate to worry about diversity and inclusion in the workplace, a connection between that goal and a psychologically safe workplace has become an area for people to think about and study and work on,” she says.

A 2015 report, co-authored by Edmondson, for example, suggests psychological safety can be an “antidote” for creating a workplace that benefits from a diversity of backgrounds, thoughts, and experiences.

Fostering a Psychologically Safe work environment

As our understanding of psychological safety grows so does our understanding of how it’s developed, nurtured, and scaled in the workplace.

According to Dr. Edmondson, author of The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth, people must be allowed to voice half-finished thoughts, ask questions from left field, and brainstorm out loud in order to create a culture that truly innovates.

“In particular, people in positions of power or supervision can and do create more psychological safety when they ask more questions, listen to the answers, and when they acknowledge their own shortcomings,” Edmondson says. “By shortcomings I don’t mean terrible failings, I mean saying ‘I’m not an expert on that; I’ll rely on your input there,’ or ‘I might have missed something; I’d like to hear from you.’”

Edmondson explains that these often-subtle invitations for candor and honesty breed a culture where employees feel comfortable bringing forward ideas, admitting to their mistakes, and providing honest feedback without fear of repercussion.

“Ordinary statements of opportunity for others to contribute makes a big difference; asking good questions makes a big difference; having a productive response to someone suggesting a crazy idea or admitting to a mistake makes a big difference,” she says. “These are micro-interpersonal interactions that by and large invite and don’t punish candor when it comes along.”

Psychological safety often also requires a degree of emotional intelligence on the part of the leader. Key attributes of emotional intelligence—including courage, curiosity, and self-awareness—are all important prerequisites.

“Psychological safety is generally built in the gray zones,” she says. “It’s built in the moments where you mess up and you have to clean up your mess, in how you own that behavior, and in how you speak to your missteps.

Practices that promote Psychological Safety

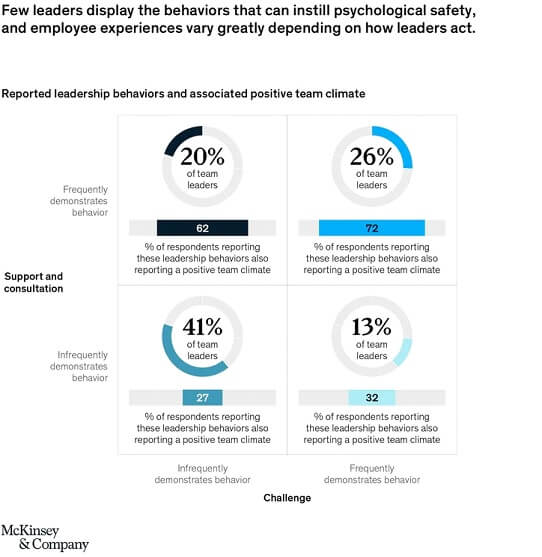

As the pandemic has demonstrated, organizations run better when employees feel a high level of trust in their company. They need to feel comfortable to ask for help or offer new ways of thinking to adjust to a new normal. However, not many leaders are able to demonstrate the positive behaviors that can provide psychological safety for workers, according to a recent McKinsey Global survey. Their research has shown that a “positive team climate—in which team members value one another’s contributions, care about one another’s well-being and have input into how the team carries out its work—is the most important driver of a team’s psychological safety.”

Psychological safety can be built upon or broken down in just about any workplace interaction, but there are some specific policies and practices that can help foster a more psychologically safe working environment.

For example, hosting regularly scheduled town hall meetings where any member of the organization can pose any question or idea to upper management. Just hosting the meeting, however, isn’t enough. Leaders need to authentically demonstrate how they’re taking ideas, complaints, and suggestions seriously in order to encourage others to participate, share their ideas and speak up.

Conduct pulse surveys asking questions on a frequent basis about aspects of psychological safety, like “Do you feel like you can bring your ideas forward? Do you feel like you’re being heard? Do you feel safe bringing feedback to your boss or manager?” Getting frequent feedback will help leaders increase self-awareness around how their leadership style and behaviors impact team member’s contribution and illuminate when and how psychological safety is being built, and when it’s being broken.”

Psychological safety isn’t about being nice or polite, which is a common misunderstanding, but about being honest, transparent, and authentic. That mindset also extends to conflicts and difficult conversations, even terminations; it’s not about being agreeable or liked, but about being constructive while demonstrating emotional intelligence and cognitive empathy to arrive at a mutually beneficial outcome.

Positive conflict is what differentiates a psychologically safe environment from an environment that seems to function on the surface. Some of the nicest environments are the least psychologically safe, but when you can engage in positive conflict and constructive feedback with care and candor—when people can say hard truths to each other—that’s when you really know you have a psychologically safe environment.

Petra Russell

Petra graduated from Pforzheim University of Applied Sciences, Germany with a Masters in Design and moved to the United States to start her career as a freelance designer for Umbro/Kaepa, developing high-performance sports apparel for the US Olympic team in collaboration with Georgia Tech, School of Fiber and Engineering, and Dupont.